Feminist poetry and pumping milk

A conversation with poet and essayist Heather Lanier

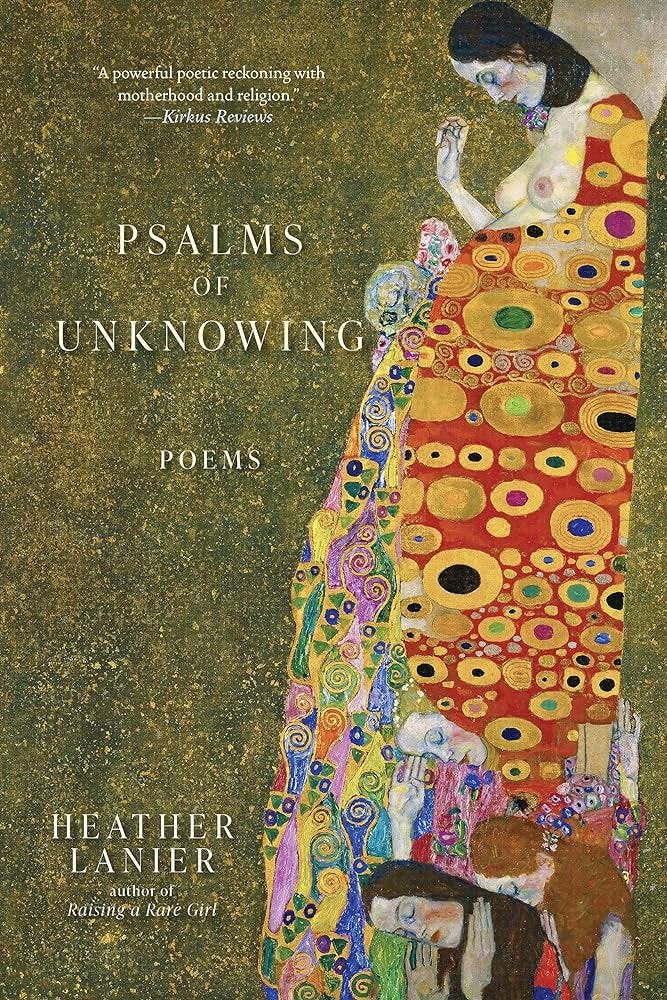

When I opened Heather Lanier’s new book of poems, Psalms of Unknowing, it’s fair to say I was smitten from page one. “Pumping Milk” explores the bizarre experience of pumping somewhere public (in this case, an office):

But it’s this bare moment before

that stuns me, dangling braless

like half of me is made

for spring break gone primal,

the other half

will write a memo.

I laughed aloud at that final phrase (“the other half will write a memo.”) Then I shared the poem on Instagram, where it immediately elicited fire emojis and “ordering this book right now” responses from friends.

Psalms of Unknowing (what a title!), explores the intersections of motherhood, feminism, and spirituality. The poems seek to reconcile the world’s heartbreak with our longing for its divinity. Psalms of Unknowing reminds me, in the best way, of Beth Ann Fennelly’s collection Tender Hooks—equal parts soft and biting, tender and untamed.

I first encountered Heather’s writing in her memoir Raising a Rare Girl, absolutely one of my favorite books of 2020. The book is her attentive, warm, fierce telling of raising her daughter Fiona, who has a rare syndrome. I’ve followed Heather’s work ever since and was delighted when she agreed to talk with me about writing, seeking, and parenting as a spiritual practice.

As someone who has spent many hours strapped to a breast pump, I can attest that pumping is one of the least poetic activities imaginable. So I love that this collection opens with the speaker “topless at the office / like a scandal.” You address the absurdity of this common (but rarely visible in literature) experience, and then use it as a launching pad to ask questions about what it means to be human.

Why begin Psalms of Unknowing with this poem?

Heather: Hah! Yes, I guess pumping milk is generally not considered pretty poetic. But my favorite poetry takes something we’d consider “Not Poetry” and somehow flips it on its side, finds meaning in it. I loved the idea of starting with that half-naked woman making sense of the absurdity, not just of pumping milk, but of life. That opening poem encapsulates so much of the collection—motherhood, feminism, spiritual questioning. So I thought it was the perfect “come on in” gesture for the reader.

You’ve said that raising Fiona, who has a rare syndrome called Wolf-Hirschhorn, helped you extricate and unlearn the ableism you’d unconsciously absorbed. The poems in Psalms of Unknowing address ableism in the context of motherhood, but they also turn to subjects like racism and gun violence. Has advocating for your daughter trained your writerly attention more closely on other injustices?

Heather: No, I’ve always leaned toward social justice. My writer’s mind has always gone there. But being a mother has tuned my heart to be more on fire in response to those injustices, if that makes sense. I feel the losses of others even more deeply than before.

You wrote Raising a Rare Girl while parenting small children, one of whom is disabled and requires far more appointments and therapy and advocacy than most children to access the same spaces.

How did writing poems compare to writing a book-length memoir? (I think of how Jazmina Barrera wrote Linea Nigra in short, fragmented essays during the first year of her son’s life, and of how poet and mother of six Lucille Clifton kept her poems so brief). Did writing poetry feel more compatible with parenting young kids than writing prose?

Heather: For me, genre is more about subject matter. Pregnancy was so weird and wild that it suited itself well to poetry. It also lacked necessary backstory or thorny plot. If I say “32 weeks” in a poem and reference a belly, everyone knows what I mean. But writing about my daughter Fiona’s syndrome—that was tough in poetry. It’s too particular, too different from the standard parenting experiences. The collection contains a few poems about parenting a kid with disabilities, but overall, that story is told in prose—blog posts and longform essays, and eventually a book. I should note that I was only able to write that book once both my kids were in school. Until then, I had to make do with shorter forms.

In your writing, parenting practices and spiritual practices are often in conversation. Our culture tends to relegate the work of caregiving to a level far below anything transcendent—it’s considered superficial, domestic, boring.

But most parents and caregivers, I think, understand the potential for transformation that even mundane tasks can hold. In what ways can parenting and spiritual practices enliven each other?

Heather: Oof, so many ways! I’m gonna reference a Christian thing here, so bear with me. In a letter, Paul talks about Christ “emptying” himself on the cross. We do mini versions of this in parenting all the time. As a mother, I felt like I got stripped of self very early on. After my first daughter was born, I couldn’t even find my glasses. And then the constant wake-ups, the feedings, the forgetting to shower, the bowing to the altar of the dirty diaper at a ridiculously dark hour. Parenting is an emptying of self, again and again, in service of something larger.

Any religion worth its weight is going to point us beyond our small selves. Because it turns out, while we really want to be happy, we’re kind of terrible at knowing what will make us so. (See: tagline on Amazon trucks.) Burping a baby at three a.m. doesn’t make me “happy” in the easy sense of the word. But it puts me in connection with something larger than myself, w that divine Self-with-a-Capital-S. Surrender is one way to get there, and parenting requires loads of surrender.

Any religion worth its weight is going to point us beyond our small selves.

Psalms of Unknowing is structured in four sections, after a familiar Christian blessing. But you tweak the benediction: I: In the Name of the Mother; II: And the Child; III: And the Holy Unknowing; IV: Amen. How did you land on this structure? Can you say more about the section titles?

Heather: These section titles came to me late in the game. As I was putting the collection together, I noticed that a few poems expressed a longing to rename and reclaim Christian rhetoric from a feminist perspective. That was an entirely autobiographical urge. For a long time, I struggled to sit in church and hear about all these dudes, hear all these masculine pronouns. So, I used the section titles to echo the Trinity, only in feminine and gender neutral language.

But each section title also has a double meaning. Section one, “In the Name of the Mother,” is largely about pregnancy. The mother is preparing to bring a child into a pretty uncertain world. In the second section, “And the Child,” the baby’s out in the world. The fourth section, “Amen,” offers spiritual solace after the third, “And the Holy Unknowing,” raises some political and spiritual questions. In this way, the whole book serves as prayer, one filled with longing and doubt and sass and grief and reverence…. you know, all the ways we show up in prayer.

The whole book serves as prayer, one filled with longing and doubt and sass and grief and reverence…. you know, all the ways we show up in prayer.

Do you have any anchoring creative habits or spiritual rhythms?

Heather: My anchoring habits are in my spiritual life. Every morning, I practice centering prayer for thirty minutes, and then I do a daily Examen of the day before. I try to do this before checking email or getting online in any way, and ideally, I do it before the rest of the family wakes up. Then my husband and I get the kids out the door.

My writing life is more varied, depending on the season. Sometimes I have two-hour blocks. Other times, just twenty minutes. But I aim to write for about an hour a day. I have a playlist to help me get into the zone, and I listen to it for years before I need to make another one. Sometimes I light a certain candle. When I’m really blocked or between projects, I journal. And after every day of writing, I keep a log: I record what I worked on, for how long, my thoughts about it, and then my goals for next time.

Lately I’ve been reading The Reed of God, which is a book about Mary written by a Catholic artist in the midst of World World II. It’s what you might call devotional reading, but more than that it’s a portrait of Mary’s humanity. Here’s something I underlined the other day: “If, instead of using the expression ‘spiritual life’ we used ‘the seeking,’ we should set out from the beginning and go on to the end with a clearer idea of what our life with God will be on this earth.”

I see so much of this posture in Psalms of Unknowing: a reverence for mystery while still pursuing the Divine behind said mystery. The poems are full of questions and hunger. Is that how a poem begins for you, with a question? Or do you start somewhere else?

Heather: Ooh, I love that quote. Yes, I absolutely show up in church as a seeker. I probably show up to a poem for a similar reason. I don’t know where a poem will take me, but if it doesn’t surprise me in the drafting process, I know it’s not working.

Where does a poem begin? That’s a hard one. Some poems begin with a question. Others might begin with a line or image, or even a certain conceit. It’s a mystery, what brings us to the page. But I think every poem comes from the urge to take this swirly soup inside us and give it form.

How has parenting shaped your vision of who God is?

Heather: During Fiona’s first year, we were actually living a pretty precarious life. She needed all kinds of tests to assess her basic functioning. Could she swallow? Could she handle her own saliva? Were her kidneys working? It’s just the nature of the syndrome that the first two years raise a lot of questions. We also were in uncertain financial times. We both had very temporary jobs, which meant uncertain health insurance.

All that precarity changed me. I had this sense that there was something beneath us. Not anything super cushy in the traditional sense. It wasn’t a bed of feathers below, promising exactly what our small selves wanted. But there was a loving abyss beneath us. I felt that, no matter what happened, even if it was the very worst, we would be held by love. Faith became for me, not believing in the outcome I wanted, but trusting in that “groundless ground,” so to speak.

It wasn’t a bed of feathers below, promising exactly what our small selves wanted. But there was a loving abyss beneath us.

Thank you, Heather! You’re wonderful.

Follow Heather on Instagram and find her books here and here.

Read With Me:

Beyond recommending Heather’s books, which you should absolutely read, this month I’m recommending The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese. It’s a lush and sprawling novel in one of my favorite categories, AKA stories that unspool across many characters and decades. Set on the Malabar Coast of India (where I now want to travel immediately), the plot concerns a strange condition of drowning that plagues a family for generations.

¡A bonus, non-reading recommendation! This Tiny Desk Concert with Natalia Lafourcade is sheer delight. Don’t be surprised if you catch me wearing those braids.

That’s all for this month! Thanks, as always, for being here.

Love, love this conversation. Thank you, Annie and Heather!