This is part two of a four-part Advent series about Mary. Read the first essay here.

My friends and I talk about how wild it is that the first birth we attend is usually our own. Like death, our culture tends to sanitize birth and sweep it out of sight. I had never witnessed a birth until late in my first pregnancy, when I took a deep dive into birth videos on Instagram; but even that was only watching through a screen. The first birth I attended was my daughter’s, which is to say my own.

I’ve become fascinated by the history of obstetrics, and how our cultural understanding of birth shifted from viewing it as a natural event to a problem that needed to be treated in hospitals; how midwives who carried centuries of knowledge in their bodies were pushed aside in favor of male doctors and medicine, technology, interventions. (For more on this, I recommend Angela Garbes’ book Like a Mother and Allison Yarrow’s Birth Control).

What do we miss by sequestering birth away from the home, the family, and the community at large? What did we lose in the shift from midwife-attended births in the home to doctor-attended hospital births? Certainly we lost exposure, familiarity, and comfort with the birthing process. More insidiously, we also lost the embodied knowledge of women. We lost the wisdom their hands held, the stories and practices passed from mother to daughter to neighbor to niece. (Don’t get me wrong, for complicated or high-risk births we also gained a lot, namely life-saving interventions. There’s nuance here, as with any story.)

But it’s interesting to me that birth is something most of us know so little about, even though we were all born, even though many of us will give birth or already have. Movies show pregnant women screeching on their backs in a hospital bed and then poof, a baby appears! And think about literature: we rarely read about birth beyond abstract or cursory glimpses.

Last spring, a writer friend and I were talking about our birth experiences and how transformative they felt, how we felt compelled to talk about them, how they seemed like epics that deserved the container of a story. We talked about the bias we see in art, the sense that birth stories—unlike war stories—aren’t worth depicting. And yet so many of us are hungry to see our experiences reflected on the page. My friend said something like, “Birth is all I want to read about now.”

I want to read about it too: the humor, the drama, the euphoria. I want to read about the material details of two bodies—mother and infant—working together in the throes of maximum effort to deliver life.

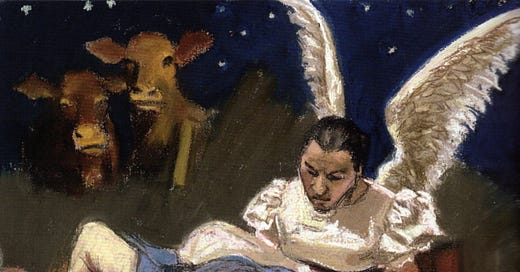

Paula Rego (Portuguese British, 1935–2022), The Nativity, 2002. Via Art and Theology.

My own labor came on slowly at first, with four nights of stop-and-start contractions that got progressively more intense until, by the fourth night, I was draped over a yoga ball in our bedroom at 2 a.m. and dozing for a few minutes before the next contraction drew back and rushed forward like a wave. (“Labor feels like a tide inside,” writes Allison Yarrow. “Even the fluid within the uterus is saline, like the ocean.”) Then, on the fifth night, my water broke and active labor came on fast and furious. Davis and I turned on our birth playlist and prepared for hours of at-home labor, but within sixty minutes he was helping me out the door and I was on all fours in the backseat of our car, clutching a plastic comb on the advice of a friend who said the sensation of plastic teeth biting into my palms could distract from the intensity of contractions. When we arrived at the hospital, the lobby was dark and deserted (here’s a helpful tip: hospitals actually close at night?). Davis couldn’t find the elevator and so he called the hospital while inside the lobby, frantically asking a staff member how to find Labor and Delivery. Meanwhile I waddled over to a trashcan and threw up the pasta I’d eaten for dinner. Even then, as I was entering transition, the most acute moment of labor, I remember thinking to myself, “Surely this is a low point.”

Which is to say: there is humor in a birth story. Along with the physicality of it all, we don’t often read about the humor. But birth can be funny. I’d love to read more birth stories that capture the shrugging vulnerability of having no dignity left as your body does what it needs to do. I look back on my birth and have to laugh at certain moments: the comb clutched in my hand; the cow sounds I heard myself making in the backseat of the car with my head pushed against my daughter’s yet-to-be-used car seat; Davis filming a quick video from the front seat that I wouldn’t see until days later; the fact that a nurse wanted to swab my nose for Covid as I was buckling with a contraction and then asked me THE BEST ADDRESS TO USE while Davis requested testily that she refer to the printed documents in her hand. It was the slapstick stuff of a comedy.

Birth can also be traumatic, its own kind of battle. “A third of women describe their birth experiences as traumatic,” writes Allison Yarrow in Birth Control. Through her research, Yarrow met a psychologist who treated mothers suffering from birth-related PTSD. “They experienced flashbacks, nightmares, hyperarousal, and reclusion. They struggled to fall asleep, then couldn’t get out of bed. They felt fear, helplessness, horror. Their own infants triggered them. Dancy found this reminiscent of what her combat veteran patients experienced.”

And of course, there’s the euphoria and transcendence of this kind of experience. Birth can be sacred. It’s easier to describe the play-by-play details of a birth; it’s harder to pin words to the feeling of drawing close to death and then surfacing, or of meeting a child you have carried for nine months, their tiny body tucked under your chin as they breath rapidly in a foreign land of light and air.

These are the kind of details I’m hungry for when I read the story of Christ’s birth.

We’re unlikely to encounter birth stories in popular culture, and we’re also unlikely to hear much about Jesus’ birth during Advent—let alone any other time of year—beyond some roughly sketched and sentimentalized details. Mary and Joseph retreat to a stable. Jesus is born, swaddled, and placed in a feeding trough. Animals and shepherds surround the Holy Family under stars. When I was pregnant and very large two years ago during Advent, I remember feeling irritated that scripture offers so few details of Christ’s birth, and that the messy, human elements of Mary’s pregnancy and labor are so rarely the subject of reflection. Why didn’t we talk about the bizarre truth that God chose to take human form in a woman’s uterus and to co-labor with her in the birth process, a process that is unpredictable and crude and not typical sermon material? Why are we so squeamish about women’s bodies and the idea that God chose to become a person within one?

It might be that we are, to quote the Catholic mystic Caryll Houselander, “afraid of birth, of the pain, the crudity, the fierceness of birth, of the responsibility of the new life.” Maybe we are afraid of the messiness of it, the femininity of it, the idea of a woman’s body in the throes of labor. Possibly it’s because the idea of Jesus emerging from Mary’s vagina is offensive. Maybe it’s uncomfortable to imagine his head crowning, even tearing her perineum in the process. Maybe we’d rather imagine a clean and swaddled Christ than an infant covered in vernix, looking damp and bedraggled, as Mary likely did too.

But I think we miss something if we fast-forward Mary’s birth, which is Christ’s birth.

During labor, mother and the baby work together. No one is entirely certain what triggers labor—is it the baby? The mother’s body? A combination? But we do know that, just as the mother’s uterus contracts to coax the baby down the birth canal and just as the cervix softens and effaces to allow for descent, that baby itself also does some heavy lifting. The baby propels their body downward by pushing off with their feet, then spins and rotates to move down a narrow passage. The baby’s head moves forward and back in a push-pull motion when it’s close to crowning, to allow the mother’s tissue to stretch, reducing the likelihood of tearing. I picture a runner rocking back and forth on the starting block, readying herself for an explosive burst of movement when the gun goes off. Birth is a process of co-laboring, two bodies working in tandem.

I read that some of the early church fathers believed Mary didn’t experience pain during labor. Maybe someone can convince me of the theological merit of this argument, but it strikes me as erasure and a fear of the female body, the very body that God chose to take shape in. It means so much to me that Mary actually did feel pain—that she bled and tore and swelled and ached. Her humanity, in all its material imperfection, matters. God chose to collaborate with her in this specific, human experience of birth.

This Advent, I am re-imagining Mary’s birth story. I wish for an unsanitized version of the nativity. I want to be reminded that birth is the stuff of epics, and that this particular birth reveals a God who collaborates with us in vulnerable and intimate ways. Mary and God co-labored together, in a very literal sense, to bring God into the world, and to bring the kingdom of God to us—that life-giving, liberating kingdom that is now and is to come. The union of human and divine is embodied in this relationship between a teenage girl and her newborn son. God was born from a woman’s mighty body, and God created her mighty body to bear Christ.

As always, so many lines I loved. But this one! “I want to read about the material details of two bodies—mother and infant—working together in the throes of maximum effort to deliver life.” 🙌🏽

This essay in particular made me look back at my own birth experiences. But all your reflections on Mary have also made me very curious about my own relationship with the Virgen de Guadalupe 💖